Message of congratulations to the Springboks from Henley Africa

The scenes of joy resonating around South Africa this week after the Springboks’ watershed Rugby World Cup final on Saturday are as real and as...

The title of this article is inspired by a conversation I had with Barry van Zyl about music and performance. It occurred to me that this is a placeholder for life, as regardless of one’s art or endeavour, this is how we navigate continuous learning and mastery. At any moment we are the sum of…

The title of this article is inspired by a conversation I had with Barry van Zyl about music and performance. It occurred to me that this is a placeholder for life, as regardless of one’s art or endeavour, this is how we navigate continuous learning and mastery.

At any moment we are the sum of what we know and are good at, and what we are learning and not good at, yet. We are equally the sum of what we don’t know, and what we think we know for sure.

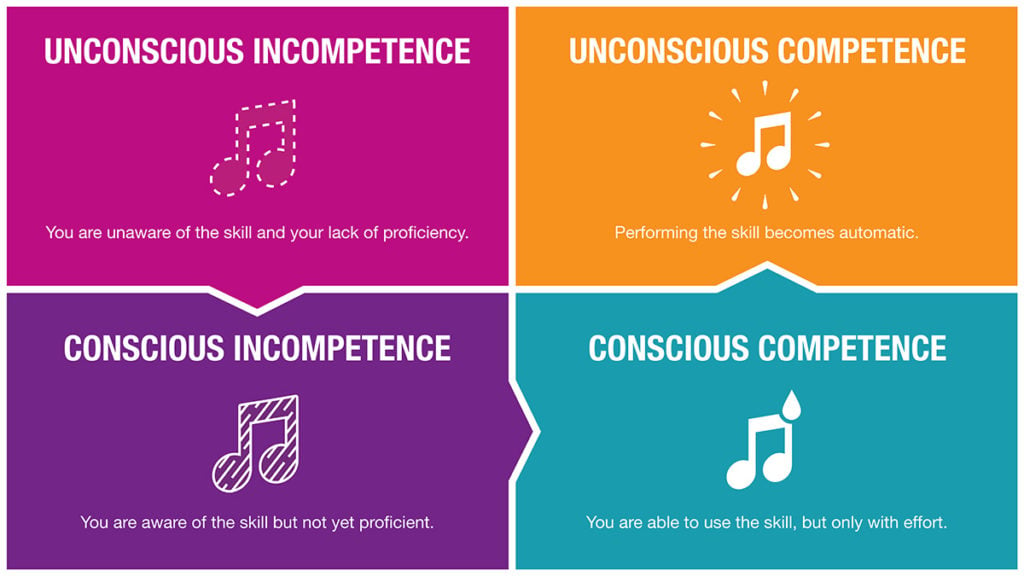

The four stages of competence illustrate this nicely. Originated by Martin M. Broadwell in the late 1960s as “the four levels of teaching” and iterated by Noel Burch in the 1970s as “the four phases for learning new skills”, this unique illustration is designed by Sienna Lee using a music eighth note as the ‘competency reference’.

Graphic by Sienna Lee

Importantly, conscious competence does not denote enjoyment. You may be a competent driver and loathe driving. However, deliberate (mindful) practice to progress your competence is a conscious endeavour. Conscious incompetence can indeed be frustrating, and equally, it can be motivating if you are driven to advance to conscious competence.

If you remain mindful that practice is what you can’t currently do confidently and performance is what you can, you maintain an optimum level of consciousness, regardless of whether you are experiencing the ‘creeky’ phase of learning something new or enjoying greater levels of mastery and elegant performance.

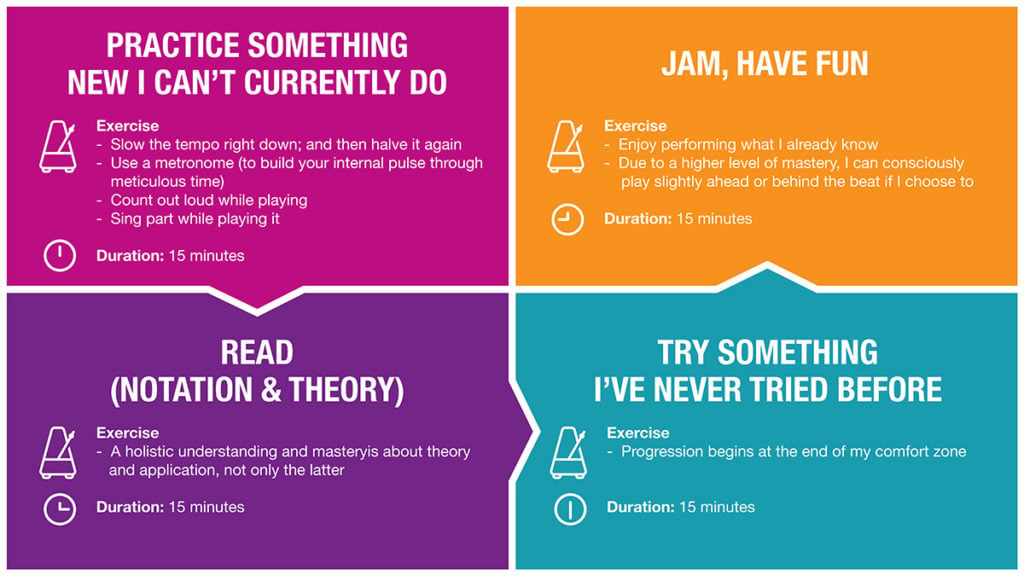

The ‘perfect’ image of successful individuals and organisations distorts the reality of discipline and hard work (often over many years) that has resulted in this success. As continuous learning can seem overwhelming, I have paraphrased Barry’s 60-minute music practice schedule below. This framework is adaptable to any learning scenario. As we’re often learning and mastering simultaneously, this is a wonderfully simple system for simultaneous progression and fulfilment.

Graphic by Sienna Lee

Barry’s schedule illustrates how much one can achieve in just an hour a day, and reinforces the principle that time spent doesn’t denote the quality of the output.

Master jazz drummer and educator John Riley reflects,

“I used to think I needed two or three hours to make progress and I’ve discovered that’s not true at all. If I have 10 minutes and sit at the instrument, something good will happen. And I’ll feel better the next time I sit at the instrument.”

When we practice, we get proficient. When we get proficient it is fulfilling and an opportunity to share it with others. It’s not the speed that matters, it’s achieving the goal.

The scenes of joy resonating around South Africa this week after the Springboks’ watershed Rugby World Cup final on Saturday are as real and as...

Published 11 September 2020, Daily Maverick After surviving one of the longest lockdowns in the world, but with the concomitant cost to the economy...

Henley Business School Africa has awarded an MBA Creative Scholarship to Mariapaola McGurk from an organisation called The Coloured Cube. There were...

Be the first to know about new our latest newsletter insights